Are you a Luddite?

‘Luddite’ is one of those terms often thrown around as an insult that has been largely stripped of its original meaning and content.

Today, it seems to be used most often to designate people as being suspicious or opposed to AI and other new technologies.

It is vital that the left thinks through its approach to the introduction of new transformative technologies in an era of social inequality and power disparity and avoids being either over-enthusiastic about the promises of these new systems, or innately cynical and negative about potential benefits they could bring.

History does not give us the answers, but it does help orient us to the major questions we must answer as we forge a pathway ahead.

That brings us back to the Luddites.

Where did the Luddites come from?

Popular stereotypes depict the Luddites as a radical group of British workers in the early nineteenth century who smashed up new machines and technologies they feared were displacing them from their work.

This has come to be representative of a guttural rejection of technology in general – often seen as somewhat understandable, but unmistakeably naïve.

The reality, of course, is more complicated.

Let’s start with the broader context.

In the early nineteenth century, Britain was a rapidly industrialising empire at war.

This was the period of the first industrial revolution. In preceding decades, the British peasantry had experienced mass displacement with the “enclosures” of traditionally common land. New factories were opened, “dark satanic mills” in which long hours in inhuman conditions prevailed.

Collective action and organisation by the emerging working class was strictly policed (and largely illegal). Inequality was stark. The benefits of industrialisation went directly to the British elite – including its emerging class of industrialists.

The market reigned, largely unrestrained.

To make matters worse, the Napoleonic wars (in which Britain was a key part) were economically draining, driving up poverty and exacerbating suffering. Food grew scarce, with scarcity driving up prices of basic necessities, contributing to the radical mood.

The new machines of themselves did not create the inhuman conditions in which workers toiled, this was the product of the class system.

The disparities of the era were conditioned by the social power relations that prevailed. Machines created new opportunities for workers to be hyper-exploited, and many eager industrialists took advantage of this.

Who were the Luddites

This was the context in which the Luddite movement emerged.

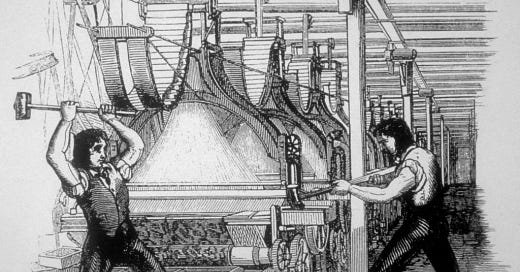

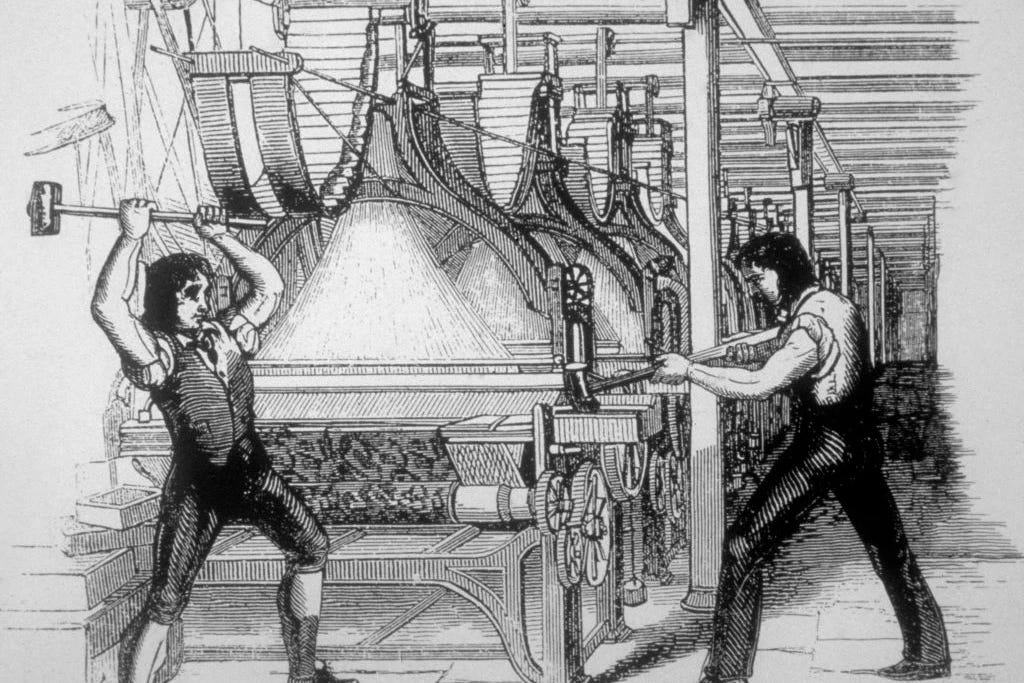

On the 11th of March 1811, British troops broke up a crowd of protestors demanding better wages in the manufacturing centre of Nottingham (well known for its textiles). In a nearby village that night, workers broke into a factory and smashed up the machinery inside.

This form of rebellion quickly spread across England. Soldiers were stationed at factory doors to defend against possible sabotage. The parliament passed a law that made the breaking of factory machines a capital offence.

Later that year, 20,000 Nottingham-based stocking industry workers lost their jobs because of new automated machinery. It is important to remember, there was no social safety net at this time. There were no industry restructuring and retraining programs to support these workers transition into new jobs. They were simply cast onto the scrap heap. Workers broke into Nottingham factories and smashed the machines that had replaced them.

As Richard Conniff has written for the Smithsonian Magazine: “the Luddites were neither as organized nor as dangerous as authorities believed. They set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered. In one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester. The owner ordered his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18. Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day.”

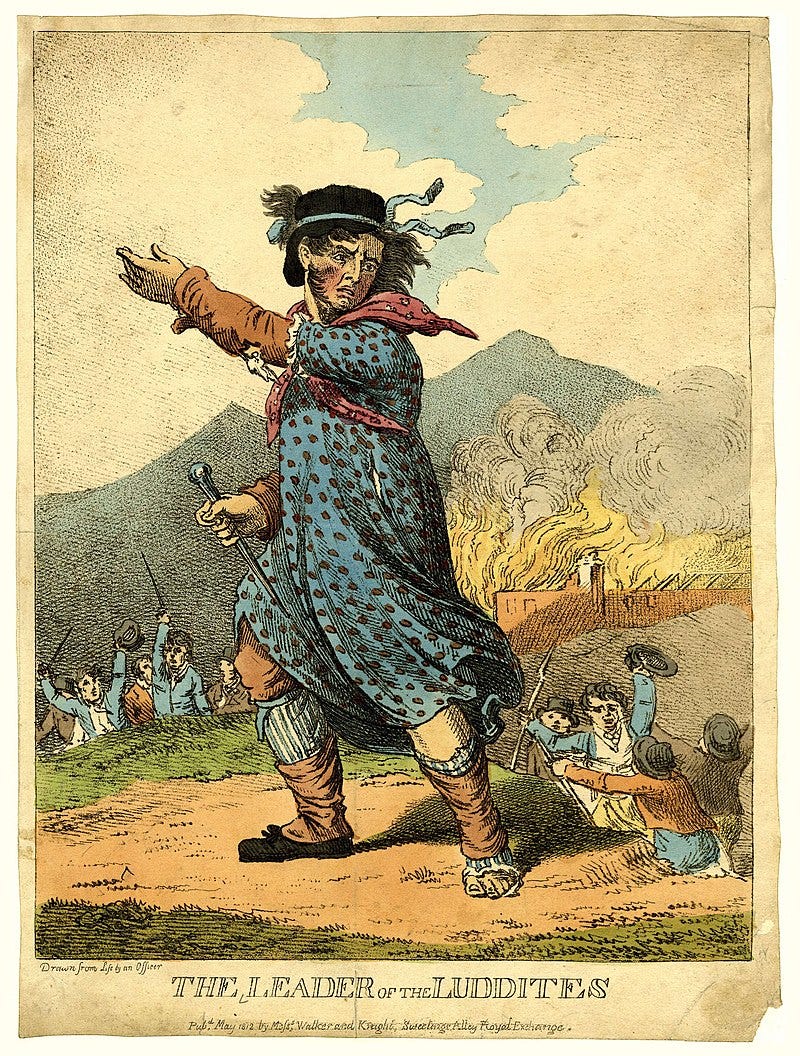

The name ‘Luddite’ came from the elusive symbolic leader of the protests, known alternatively as Ned Ludd, King Ludd, General Ludd, or Captain Ludd – who was said to live in Sherwood forest (like another mythical English fighter against tyranny).

Ned Ludd was a fictional creation of the protestors, based on a supposed incident that took place in Leicester more than 20 years before, where a young apprentice named Ludd had used a hammer to flatten a stocking frame in defiance of his employer’s tyranny.

Luddites signed declarations and letters to newspapers as King Ludd, burnishing the myth and stoking elite fears.

It is important to note, Luddites were not indiscriminate in their destruction of machinery.

They tended to target establishments owned by manufacturers who they believed were using machines to undermine standard labour practices. This included paying decent wages and hiring workers who had undergone an apprenticeship in the trade.

Their primary concern was not getting rid of all industrial machinery – and, indeed, there is strong evidence in their accumulated writings that they looked favourably upon machinery that would enhance employment opportunities while producing more goods while paying decent wages.

We shouldn’t get too nostalgic about the Luddites. Unrestrained crowds did also attack factory owners, state authorities, and others.

The protest was conditioned by specific factors of the time: punitive treatment of collective organisation meant that the movement was driven underground, ensuring a secretive and conspiratorial – and often spontaneous – character.

As Miriam A Cherry, Professor of Law, and Associate Dean for Research & Engagement at Saint Louis University Law School, has explained:

“the Luddite movement was a reaction born of industrial accidents and dangerous machines, poor working conditions, and the fact that there were no unions to represent worker interests during England’s initial period of industrialization. The Luddites did not hate technology; they only channelled their anger toward machine-breaking because it had nowhere else to go.” (ps: check out the interesting article this is from, it introduces a work of alternative fiction where the Luddites were successful in a Future Encyclopedia: https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-future-encyclopedia-of-luddism/)

But it should be seen as what it was: an organic mass movement revolting against the genuine social harm caused by many unscrupulous industrialists determined to use new technologies to hyper-exploit their workforces.

What happened to the Luddites?

The Luddite’s were unable to impede the march of new technology – and the determination of employers and government to crush their movement.

There were a number of executions of Luddite leaders and participants. In January 1813, 14 were executed on one day.

George Mellor, one prominent Luddite leader, was found guilty of murdering a local factory owner and executed.

As the historian Tony Moore has shown, some Luddites were transported as convicts to Australia.

The protest movement was unable to sustain itself, and was extinguished under the weight of employer intransigence and state repression.

As is often the case with protest movements, the Luddites have been stripped from their context.

The meaning and significance of their protest has been extracted from their story.

They have been reduced to little more than stereotypes, spectres from the past that can be dismissed because they can be so easily ridiculed.

I am not suggesting this was a conscious process of meaning distortion – but it is notable how neatly such changed representations have matched the priorities of the powerful elite who have tried to dismiss any contestation over how machinery, automation, and new technologies are introduced (and how they shape quality of life) as simple opposition to progress.

But, in reality, it has very rarely been the case that workers’ movements have opposed new technology per se.

Rather, they have opposed these technologies being used by corporate elites to undermine wage standards and conditions, to cut jobs without support for workers, and to institute dehumanising labour practices.

In other words, workers have tended to not oppose machines. They have opposed being treated like machines through the use of dehumanising work practices structured around new technologies.

One final thing

You may or may not be aware that the famed (though generally quite terrible) poet Lord Byron wrote a poem praising the Luddites, whom he had also defended in parliament in a speech to the House of Lords.

To take us out, here is Lord Byron and his “Song for the Luddites” (1816):

As the Liberty lads o'er the sea

Brought their freedom, and cheaply with blood,

So we, boys, we

Will die fighting, or live free,

And down with all kings by King Ludd!

When the web that we weave is complete,

And the shuttle exchanged for the sword,

We will fling the winding sheet

O'er the despot at our feet,

And dye it deep in the gore he has pour'd.

Though black as his heart its hue,

Since his veins are corrupted to mud,

Yet this is the dew

Which the tree shall renew

Of Liberty, planted by Ludd!

Great essay