This is the story of how women workers in the clothing industry in the 1880s defied the sexist stereotypes of their time, took strike action, and won against all the odds.

It ends with an historic victory and the creation of what is generally regarded as Australia’s first union of women.

But it begins in a slightly unexpected place.

It begins with Isaac Singer inventing a new sewing machine (the Singer Sewing Machine) in 1850.

The Singer company tells the history of this innovation: “While it took 14 hours to sew a man's shirt by hand, it took just one hour and 16 minutes with Singer. When the calendar hit 1860s, 400 Singer machines were able to do any piece of work that may be done by two thousand workers.”

In Australia, in the late 1860s/early 1870s, the Singer machine transformed the clothing industry.

The new machine enabled the mass production of ready-made garments. Much of the industry had previously been based on skilled male tailors conducting (or overseeing) the work of producing items that were sold (to order).

The concept of ‘skill’ was not a neutral one. It reflected the biases and assumptions of the day. A skilled worker was typically someone who had completed an apprenticeship – and access to apprenticeships were limited by, among other things, sexist exclusions.

Mass production led to the widespread entry of women workers who were not deemed to be ‘skilled’ to conduct work that previously required trained tailors.

It was not actually the case that these workers did not have an immense amount of skill and expertise – it was that this was not valued. The work that women did, and women workers themselves, were systematically undervalued.

It is important to remember the context: the Australian colonies were part of the British Empire. Imperial ideology was deeply gendered and racialised. Colonial women were expected to be wives and mothers, and this limited their access to the labour market. Engagement in the world of work was expected to be temporary (either before marriage or during widowhood).

The entire economic and industrial structure of society was framed around forcing women into dependence on men by denying them economic independence.

Male employers used this to hyper-exploit women workers.

The new machines facilitated the rise mass factories with appalling conditions.

There was also the growth of ‘outwork’ – work outside of the formal factory system. This was often conducted either in the home, or in makeshift workshops. Usually, a middleman would distribute work out of the factories to women outworkers. Sometimes this was done with a small group of women workers toiling in a makeshift workshop in appalling conditions. Outwork continues to exist today.

Women workers in the industry suffered an immense physical and mental toll from this work. Tailoresses remarked on being treated like ‘slaves’, having no life outside the rhythm of the machines – and of being treated like machines themselves.

And then something extraordinary happened.

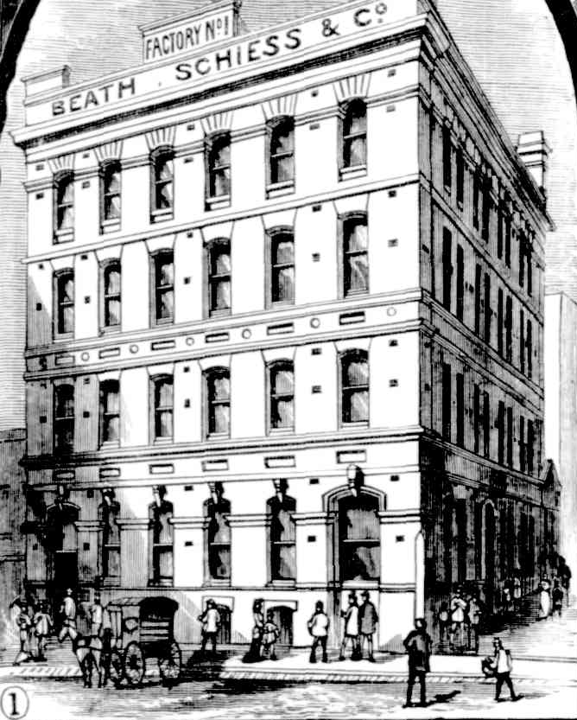

In December 1882, the company Beath, Schiess and Co in Melbourne announced it was cutting rates paid to its women workers by 10% ‘in order to meet business requirements’.

This was on top of another 10% reduction made just weeks before.

Women workers at this company (main factory in Flinders Lane) were defiant – they refused to accept this slashing of pay.

They went on strike!

The sexist company owners were completely shocked by this.

Beath. Schiess and Co. complained that other employers were paying a lesser rate.

They suggested to their workers that they should try to win uniform standards across the industry.

The company did not anticipate the enthusiasm with which their workforce took up this proposition – they decided to do just this, but to start at Beath, Schiess and Co.!

Early in the dispute, the company decided to retract the cut in rates, but was shocked when the tailoresses responded that the were not content to return to the former status quo, they were now insisting on even higher pay then they had received before.

In mid-December, between 400 and 500 women workers from the industry gathered at Trades Hall.

One of their leaders, Ellen Cresswell, moved the motion: That this meeting of tailoresses form themselves into a union for their mutual protection and improvement.

A new union had been formed.

The Tailoresses received widespread support for their struggle.

The Trades Hall Council called on all unions to support ‘our sisters in labor’.

Male-dominated unions donated at least £2,000 to sustain the strike, though some male unionists remained hostile to the very notion of women in the workforce.

The Tailoresses were determined to win. By the end of December Beath, Schiess and Co agreed to their demands – but with a condition.

The Union would have to win all employers in the industry to accept the ‘log’ of demands.

So the struggle continued.

The Tailoresses utilised their collective industrial power to better their lot. At a February meeting, women workers at thirteen other factories determined to take strike action to force their employers to agree to union rates.

Within two weeks a new log of conditions had been agreed between the Tailoresses and the newly formed Clothing Manufacturers’ Association, representing employers.

Continued intransigence from some firms required further negotiation, and a final agreement was reached in May 1883.

The Tailoresses had won!

The Tailoresses’ victory was an extraordinary accomplishment – and it had defining effects.

The new union had won improvements in wages and new protections of standards in the industry.

The Tailoresses challenged the sexist stereotypes of the time – they insisted on being paid their worth.

They had brought an unprecedented amount of public attention to the appalling working conditions that existed in Victoria’s factories.

And perhaps most importantly of all, they had asserted their fundamental humanity against the dehumanisation of the exploitative industrial system of the time.

It is a story that should be better known, because unfortunately, this struggle to assert the fundamental humanity of working people is all too relevant today.

But most of all, it is a story to be celebrated!

I tell the full story of the Tailoresses strike in my forthcoming history of Australian unionism, No Power Greater. You can preorder your copy from Melbourne University Press here: https://www.mup.com.au/books/no-power-greater-paperback-softback