On 28 October 1916, Australians voted in an historic referendum to defeat conscription for overseas military service.

This was an extraordinary moment in our national story. During World War One, with fierce fighting on European battlefields, Australians voted that their countrymen should choose if they would enlist to fight on foreign fields.

The campaign was an act of mass democracy with defining consequences.

When World War One broke out in August 1914, an election was underway in Australia. As a dominion of the British Empire, Australia was immediately involved in the conflict. The leader of the Labor Party, Andrew Fisher, famously promised that if he was returned to the Prime Ministership that Australia would fight ‘to our last man and our last shilling’.

Large numbers of Australian men enlisted (as did a number of women in ancillary services, as nurses, etc)

Many joined out of loyalty to the empire; some in the belief they were serving Australia; some out of a thirst for excitement; and some because drought had dried up jobs alongside the riverbanks and the army was one way to ensure a steady wage.

It should seem obvious, but these recruits were people, not numbers. No two enlisted for precisely the same reasons – and none knew what the world’s first industrial war would be like.

The labour movement followed Fisher’s lead. Many union leaders noted regret that it had come to war, but backed in the war effort once the conflict broke out. A small minority of socialists opposed Australia’s involvement in the conflict altogether.

Studies have shown that workers enlisted in much greater numbers than their ‘social betters’ – the wealthy elites. Michael McKernan’s history of Victoria during the war period reveals that over 2000 young men from the staunchly working-class suburb of Richmond went to fight, while the patriotic middle classes in Camberwell contributed just 255. So many members of the Australian Workers’ Union signed up that representations were made by the union to have a battalion formed solely composed of those holding AWU tickets.

Though generally supportive of the war effort, unions expressed fears that workers would suffer disproportionately as a result of the war, if measures were not taken to ensure they would not pay the biggest price of the conflict.

The conduct of the war confirmed these fears. The working class was disproportionately bore the cost of the war, whether on the shores of Gallipoli or economically at home. Working-class families were gripped by anxiety over the fate of sons, husbands and brothers overseas, and this was matched with trepidation at home as prices rose and wages stagnated.

This disquiet was briefly contained by the Labor Government’s 1915 promise to pursue a referendum to secure power over prices – to stifle the price gouging engaged by some big businesses that were taking advantage of the disruptions of war to fatten their profit margins.

But in late 1915 Andrew Fisher resigned the Prime Ministership, and was replaced by the belligerent and mercurial Billy Hughes.

Hughes outraged the labour movement by stepping away from the referendum. His alibi was a supposed deal with state premiers to voluntarily cede these powers to the commonwealth. They didn’t.

Matters were worsened when Hughes departed for Britain on a lengthy tour. Australian troops were increasingly being transferred to European battlefields, mired in bloody trench warfare. Rumours circulated that Hughes was being persuaded to introduce conscription to replenish troop numbers as casualties mounted.

The union movement determined to take action

In 1916, the AWU declared its opposition to any attempts to introduce conscription to compel Australians to fight in Europe. The union supported workers voluntarily enlisting, and promoted conscription for home defence. But it did not believe Australians should be forced to fight on another continent.

Other unions and Labor Party branches began to follow.

Unions assembled in a national convocation in Melbourne’s Trades Hall: the All-Australian Trade Union Congress (AATUC).

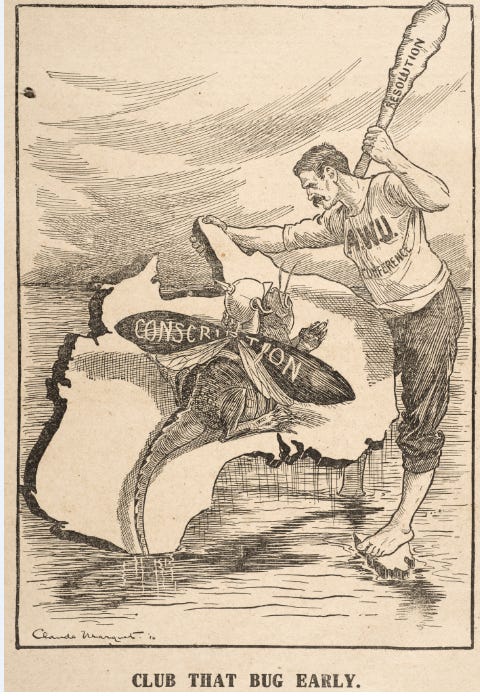

This national gathering declared its ‘uncompromising opposition to the Conscription of life and labor’, and promised to organise against ‘any attempt to foist Conscription upon the people of Australia’.

At this meeting, it was agreed that the union movement would initiate a major national campaign to oppose any attempt to introduce conscription. Later, Trades Hall was raided in the dead of night to seize an anti-conscription manifesto produced by the campaign’s national executive.

Soon after the AATUC Hughes returned to Australia. There was immense speculation as to what his intentions would be.

He didn’t realise it, but Hughes was already at a disadvantage. The union movement had set in place a national campaign based in Melbourne (then the national capital), while the Easter Rising had solidified anti-conscription sentiment among Irish Catholics, who viewed the British Empire with increasing hostility.

On 30 August 1916, Hughes announced that a ‘referendum’ (in reality, a plebiscite, as it would not affect the constitution) would take place. The vote was called to alleviate Hughes’ political difficulties: he knew his own Labor senators would not pass the measure against union opposition, and hoped instead that a plebiscite would instil his measure with popular legitimacy.

The campaign had begun.

The pro-conscriptionists used every rhetorical legerdemain they could conjure in an attempt to bulldoze the union opposition, such as appealing to working-class voters not to ‘scab’ on their mates in the trenches by voting ‘no’. Only military victory for the Allies, Hughes argued, would assure the future of White Australia – the racist policies of exclusion.

The anti-conscriptionist disagreed. The anti-conscription campaign argued that only defeating the conscription proposal would secure the future of White Australia.

It was indicative of the odious racism of politics at the time that both sides appealed to support for the racist White Australia policies, a racist reality we should neither excuse nor forget.

But the anti-conscriptionists did not solely appeal to racism. To them, conscription was a mark of militarism and imperialism. It was an assault on democratic rights, and on the gains of trade unionism. Where conscription for military service was implemented, they argued, conscription for industrial service – and a concomitant destruction of union standards – was sure to follow.

It required bravery to make such arguments. Acts of physical violence were common, often by mobs of soldiers.

John Curtin was appointed as Secretary of the campaign’s national executive (his first role of national prominence). He was advised to leave his shoelaces untied when he gave speeches on platforms along Melbourne’s Yarra River, so he could kick them off more easily if he was thrown into the water.

Women were actively involved on both sides of the campaign. In Victoria, a Labor Women’s Anti-Conscription Committee was formed, among its leading activists was Muriel Heagney, who would become the leading activist for equal pay after the war.

The committee organised public meetings and speakers’ corners, and canvassed suburb by suburb; working-class women, meanwhile, regularly interrupted the meetings of pro-conscriptionist forces, shouting down or clapping out ‘pro’ speakers.

In the final count, conscription was defeated – albeit narrowly.

This was an extraordinary moment in Australia’s history – with defining consequences.

By the time of the ballot, Hughes had already been expelled from the NSW Labor Party. In December 1916, this was confirmed by a national conference of the party (on a motion moved by future Labor PM James Scullin).

Hughes had been consigned to the ranks of Labor ‘rats’ – as apostates from the party were colloquially known.

The conscription defeat entered Labor legend, a moment in which mass democracy overcame potential tyranny.

If you are interested in finding out more, I tell the story of 1916 in deeper detail in my book Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin. You can find out more at the Melbourne University Publishing website.