Medicare at 40: contested origins

Did you know how close we came to not even having a universal health insurance scheme in Australia?

On the 1st of February we marked the 40th anniversary of Medicare coming into operation. But did you know how close we came to not even having a universal health insurance scheme in Australia?

The first universal health insurance system was introduced under the Whitlam Government, and was known as Medibank.

Bill Hayden, who we sadly lost last year, played a defining role in Medibank’s creation as the Minister for Social Services. Universal health insurance was an article of faith for Whitlam. It was about ensuring that healthcare was a universal right that all Australians could access.

This was strongly opposed by the Coalition.

The Coalition wanted to maintain an individual insurance model – basically the same system as in the United States, where your quality of healthcare was determined by how much you could pay. Coalition intransigence led to the Medibank Bills being among those that triggered the 1974 Double Dissolution election. Despite the government’s clear mandate, the Coalition continued to oppose Medibank.

On the 6th and 7th of August 1974, Whitlam held the famous ‘joint sitting’ of the Australian parliament in which the House of Representatives and the Senate met jointly. Among the 6 Bills debated (and passed) were those that created Medibank – a universal health insurance scheme.

The Bills were passed 95-92. Guess who the 92 were.

Liberal Party leader of the time, Billy Snedden said: “If this health scheme goes through, this generation will be passing on a vast failure and those who vote for it will regret it.”

They didn’t.

Medibank was a crowning achievement for the Whitlam Government. But delays while further negotiations took place with the states meant that it did not come into operation until the end of 1975.

After the Whitlam Dismissal and the December 1975 election, the new Coalition Government under Malcolm Fraser wasted little time in trying to undermine the system.

In 1976, Fraser introduced a levy of 2.5% on taxable income. Holders of private insurance could opt out of this.

The government also removed subsidies for private health insurance, and other benefits that helped people pay for private insurance.

All of this was seen as a way to undermine the universal system.

While Labor was in disarray following its electoral defeat, the union movement emerged as the strongest defenders of Medibank.

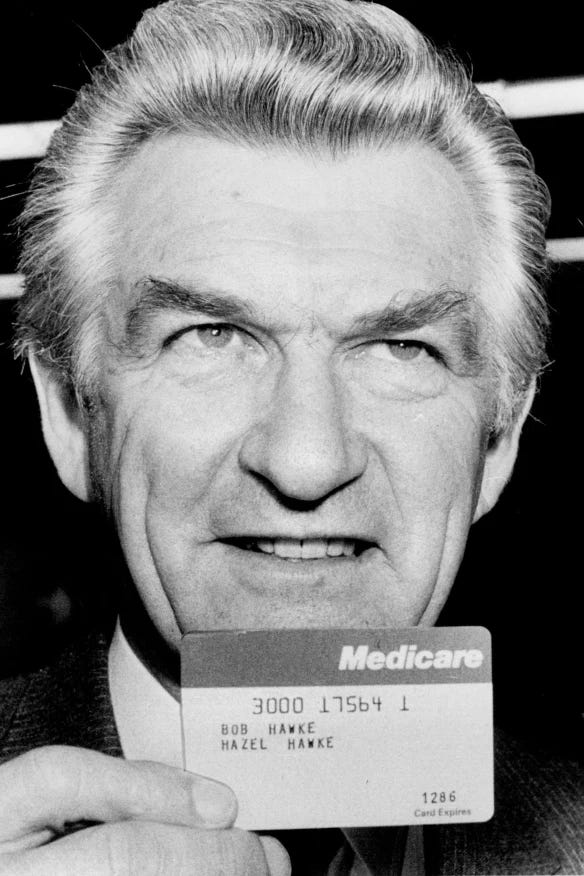

On 12 July 1976 the ACTU, under the leadership of President Bob Hawke, led a national strike to defend Medibank - often referred to as Australia’s first national general strike.

There were estimates of 2 million workers participating.

Bob Hawke explained the union position:

The Australian Government’s health insurance scheme adds to the burden borne by the individual, and in terms of total community resources allocated to health insurance is far more expensive than the Labor Party’s Medibank system.

Hawke alleged that the levy changes were an attempt to encourage people to switch out of the public system.

He warned that the private suppliers had kept their prices low as a response to the competition now provided by Medibank, but if the undermining of the system was successful they would likely increase their prices rapidly.

By 1981 the Fraser Government had dismantled Medibank.

Bill Hayden, then the leader of the Labor Party, strongly supported a return to the universal insurance system. He found allies in the union movement. At that time, the ALP and the ACTU were negotiating an agreement that would later come to be known as the Accord.

The Accord focused on how they could collaborate after Labor returned to office to overcome the economic challenges of the time, and to institute major reforms that would benefit workers, and the entire Australian community.

The return of universal health insurance was central to these discussions.

Unions representing oil workers also kept the issue alive by including a claim for health insurance to be paid directly by their employers in a negotiation for a new agreement in their industry. Spearheaded by Simon Crean (who we also lost last year) of the Storemen and Packers’ Union and Bill Kelty of the ACTU, unions in the industry united to pursue this claim.

This was intended to build momentum for the return of a universal scheme.

It was hoped that a victory in that industry would send a message to employers elsewhere that if they opposed the return of Medibank (as many had its initial creation) then they would face union campaigns looking to make them pay for the health insurance of their workers. The best way to avoid this would be the recreation of the universal model.

The oil unions were successful. Momentum for the return of Medibank was growing.

In February of 1983 Bob Hawke replaced Hayden as Labor leader, and the Accord agreement with the ACTU was finalised.

The restoration of universal health insurance was central to the Accord’s plan for Australia.

The Accord was signed amid an immense economic crisis – with inflation getting out of control. The ACTU pledged that it would help deal with the inflationary crisis through wage restraint, and not pushing for certain wage claims.

In return, it was agreed that the Hawke Government would implement ‘social wage’ measures – basically reforms that would support the quality of life of working people in lieu of certain wage increases.

These reforms were non-inflationary, further assisting economic management.

The return of universal health insurance was the union movement’s major priority.

After Hawke’s landslide election in March 1983, the scene was set for a return to the system.

Medicare was legislated later that year (with full credit to Neal Blewett, the Minister for Health and Aged Care) and came into operation in February 1984.

Medicare was the product of struggle, and its creation was not inevitable. For many years the Coalition overtly opposed the system. The Liberal Party’s 1987 electoral policy document made clear its disdain for Medicare, stating:

‘Australia’s health care system is in a shambles. The real villain is Labor’s doctrinaire commitment to a universal government health insurance system, Medicare. By discouraging self-provision, by increasing health funding from the taxpayer and removing disincentives to overuse of medical services, Medicare has created a system obsessed with cost at the expense of quality, security and comfort.’

More recently, rather than opposing the system outright, the Coalition has sought to undermine it in more subtle ways. Just as Medicare’s past is one of contest, so too will be its future.

But at 40 the system stands as an enduring monument to the visionaries and reformers who believed in the innate rights of Australians to enjoy healthcare as a universal right – not a privilege.

So, a little late (but still in the right month), happy birthday to Medicare.

Watch Bob Hawke introduce Medicare to the Australian public at this link.