When John Curtin died on the 5th of July, 1945, he was deeply mourned across Australia. Newspapers declared him a casualty of war. As his body lay in state at the King’s Hall one mourner was heard to say ‘I suppose this is the first time he has had real rest since he entered this parliament.’

At a time of extraordinary crisis for Australia, Curtin was known for his dedicated and visionary leadership in guiding us through the years of conflict.

But Curtin did not just lead Australia to victory in the war – his government ensured that Australia would ‘win the peace’ as well. Curtin and his government took action to ensure that the country that emerged from the conflict would be a more prosperous, equitable, and just place than it had been before the war had begun.

Doing this required overturning an existing political and economic consensus - a deep-seated set of beliefs held by policy makers and powerful interests on how the country was supposed to be governed. This orthodoxy sought to limit the role of government and subject the individual to the whims of the market. This was an approach to political and economic management that had led to immense suffering during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Curtin and his government repudiated this set of understandings and built on the solidarity demonstrated in the war years to promise, and deliver, a new mode of governing based on collective endeavour.

This is a story that matters to us today. Over the past decade the Coalition government cultivated political cynicism and denigrated the positive role that government can play. Recently, other political operators have sought to capitalise on this cynicism towards politics for their own partisan purposes, practicing the politics of moral declamation and denunciation with little serious strategy on how to achieve change.

In this context, it is vital to learn the powerful lessons from Australia’s political history on what has inspired moments of transformative change, and the processes through which such change has been realised. Nearly 80 years on since his death, John Curtin’s political life remains one of the most powerful examples of the possibilities, and substantial challenges, in achieving progressive change in our democratic system.

“the materials requisite for the equipment of life”

John Curtin was born in Creswick in Victoria in 1885. His was a working-class upbringing, one that was deeply marred by the devastation of the economic depression of the 1890s. As a young man he was in constant search of employment to help support his family, but he found only procession of short-term and insecure jobs.

His experience of inequality and insecurity stoked his political consciousness. He rejected the dehumanising notion that the market alone should dictate working peoples standards of life. He joined both the Labor Party and the Victorian Socialist Party and agitated for social change.

This activism led to his appointment in 1911 as Secretary of the Timber Workers’ Union (a precursor to today’s CFMEU Manufacturing Division). He represented workers in this dangerous and difficult industry, roaming Victoria from camp to camp to meet his members and learn their concerns.

Curtin opposed the outbreak of the First World War, arguing it was a war for European Empires, not Australia. He believed that the working class would sacrifice most both on the frontlines and on the home front.

Curtin noted that the government intervened in the economy on an unprecedented scale during these years to facilitate the war effort. If the government could use such powers to wage war Curtin argued, then ‘it is imperative, urgent and logical that it organise factories, workshops, mines, farms, and forests to supply the materials requisite for the equipment of life.’

But this ran counter to the prevailing assumptions of policy-makers and economic experts, who argued that such matters should be determined by market forces alone. Profits kept rising. There were bread riots in Melbourne.

During the war Curtin came to national prominence when he led the union campaign against conscription for overseas military service in 1916. The following year he left Melbourne to edit the AWU-backed Westralian Worker newspaper in Perth. In 1928 he was elected as the Federal Member for Fremantle.

“who by virtue of his or her citizenship is entitled to a reasonable subsistence”

When Curtin came to Canberra, Labor had been out of office since 1916 when the party had split following the conscription vote.

In 1929 James Scullin led Labor back to power. Scullin had been arguing through the 1920s that the conservative Bruce government’s excessive borrowing on international money markets was exposing Australia to a potential financial shock. Just days after he was elected Scullin was proven right, and the Great Depression erupted.

Scullin sought to formulate a response to the cataclysm that would not result in workers paying the price for a crisis they had not created. He was opposed at every step by conservatives who still controlled the senate, and right-wing policy makers across the government and financial sector who scuppered his every move.

The conservative intransigence was born from the prevailing orthodoxy of the time that insisted that the market must be set free to resolve its own crisis. Conservatives argued that the only way out of depression was to cut wages and reduce government spending – no matter the human cost.

When that didn’t work they had a new solution: cut even more!

Curtin was a backbencher, and largely powerless to shape events. So he spoke and he wrote about how vested interests and the conservatives were leading the country to ruin. He argued that it was workers, once again, paying the price.

On one occasion he stood in parliament, and against howls of opposition from conservatives argued that government had a responsibility to ‘honour our obligation to every man and woman in this country, who by virtue of his or her citizenship is entitled to a reasonable subsistence.’

Curtin was arguing that the ultimate responsibility of the government was not to the abstract notion of “the economy” (which to the conservatives meant little more than the balance sheets of the big corporations and banks) but to the Australian people. A basic right of citizenship, to Curtin, was the support required to live a decent life.

But it was the market-driven orthodoxy won out, and the effects were devastating. Curtin lost his seat in the anti-Labor swing at the 1931 election. Labor did not regain office for a decade.

“no less grievous than the devastation of war”

When the Second World War broke out Australia was led by a conservative coalition headed by Robert Menzies. In a time of dire need, Menzies proved himself to be ill-suited to leadership.

His government’s response lacked clear direction. Preoccupied with petty bickering, the conservative coalition frayed. Menzies resigned in 1941, to be briefly replaced by Arthur Fadden. But the conservative coalition had discredited itself.

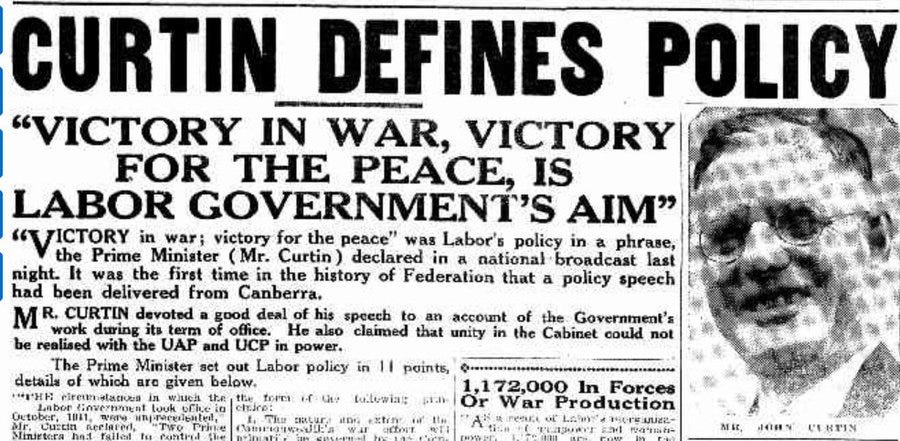

In October 1941, two independent MPs withdrew their support of the splintered and directionless conservatives and provided confidence to Curtin’s minority government.

Curtin understood something that the conservatives could not: the demands of the war required a collective response.

He called upon Australians to sacrifice, together, for the greater good. But he also promised that sacrifice would be redeemed once the war was won.

Curtin’s government pledged to deliver ‘Victory in War – Victory for the Peace’.

It promised there would be no return to the ‘horrors of starvation, unemployment, misery and hardship no less grievous than the devastation of war’ that had marred Australia after World War One and during the Great Depression.

Curtin’s government swept aside the failed conservative orthodoxy. It demonstrated that government could play a positive role in the economy.

By doing this, it established a new governing consensus. One that would persist in the decades that followed.

It implanted a new orthodoxy that government did have a role to play in both stimulating the economy, and in providing the services that would enhance quality of life for the mass of the population. Australia continued to be plagued by exclusions and discrimination in this era, and it should not be overly idealised. But within the limitations of the time it delivered an increase in wealth and opportunity to the mass of the population on an unparalleled scale.

It was a defining achievement. It set the bounds of economic and political management for decades to come.

This was a vision of government that dated back to Curtin’s argument in an earlier war that a government that had the extraordinary power to wage total war had the responsibility to use those powers ‘to supply the materials requisite for the equipment of life’.

It was a vision developed and honed over many decades of collective struggle and endeavour as a labour movement activist, intellectual, and leader.

Curtin for Australia

Throughout his life Curtin developed a theory of government, and an understanding of its responsibility to its citizens.

It was this theory that provided Curtin with ballast as he negotiated the extraordinary crisis of the Second World War, and took action to build something better once the conflict was done.

It was a theory deeply rooted in the lived experience of the working class and steeped with the values of the labour movement. This was expressed in his government’s actions, based on collective endeavour to mobilise the country’s resources to win the war, and to win the peace.

None of this happened overnight. It required many years of intellectual labour, and honest assessment of the capabilities of change in a particular moment. The change achieved was imperfect, of course. But it fundamentally transformed the lives of millions of workers who had previously been subject to the whims of the market, consigned to urban slims, commodified and stripped of their essential humanity on the labour market.

Curtin’s extraordinary accomplishment was to take the values of the labour movement – solidarity, collectively, and mateship – and to make these the dominant assumptions upon which government acted.

Almost 80 years on from his death in office, he remains an inspiration for all those seeking to utilise the power of government to make real and substantial changes to improve the lives of Australians.

Find out more about John Curtin’s life and politics in Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin: The Making of the Modern Labor Party by Liam Byrne (Melbourne University Press, 2022).

It is available for purchase at this link.