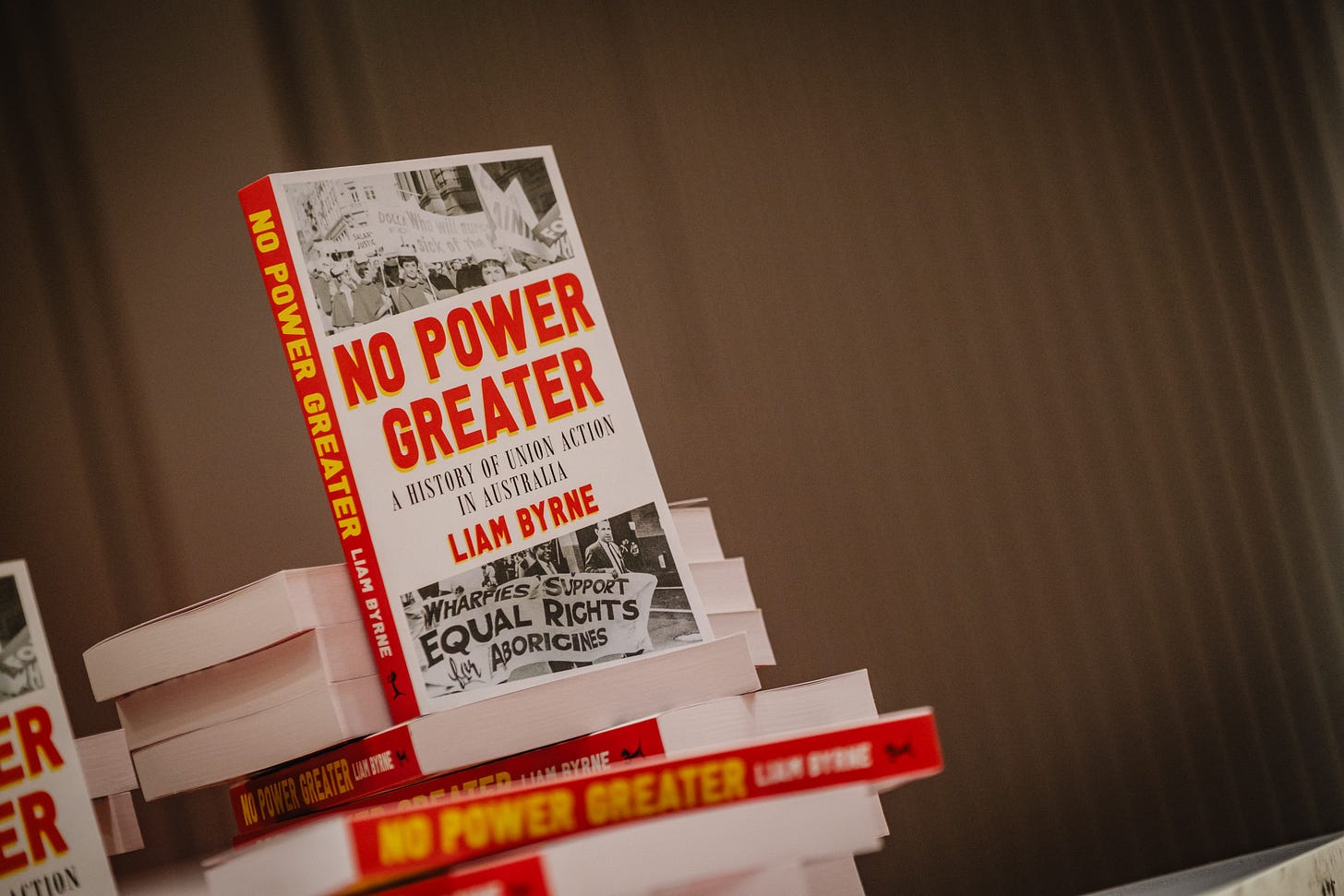

I was honoured to speak to Per Capita’s John Cain Lunch this June about my book, No Power Greater.

An edited version of the speech is available below. You can listen to the podcast version here.

You can purchase your copy of No Power Greater at all good bookstores or online.

My book, No Power Greater: A History of Union Action in Australia, is fundamentally a study of the human experience of unionism.

It seeks to understand what has inspired successive generations of working people to build, maintain, and pass on their own collective organisations – even amid all the extraordinary changes that have taken place in the workforce and the economy since unions were first formed.

In this book, I make two fundamental arguments.

The first, is that unions have remained relevant to workers because unions are driven by a fundamental humanising mission.

A drive to assert the fundamental right of working people to be treated as human beings: not as machines, or as numbers in a computing system.

The second fundamental argument of the book is that unions are more than just institutions.

They are communities.

In the book I use the term emotional communities – communities of individual workers from a broad array of background and experiences who have forged a common bond, and a common identity, through collective struggle.

These emotional communities have been defined by who they included – but also who they excluded.

This book seeks to locate exclusions in their social context.

And it foregrounds the stories of workers often at the margins of previous general union history and considers their own organising and action to challenge these exclusions and win a place in the emotional community of unionism.

This book was written as an entry point to union history.

By no means does it pretend to be the final word on any aspect of the movement’s long, complicated, and truly immense story.

I hope that those who have a long personal or academic engagement with union history will enjoy it and find it useful as it explores these two main arguments.

But the primary audience for this book are those who are still learning about what unionism is.

Who are still learning about how workers have taken action.

Why workers have taken action.

That worker action has actively shaped Australian history.

And that worker action is still relevant today.

It is written to challenge the idea that history is made only by the elite.

That history is only made in parliament – or in corporate suites.

Great transformative ideas don’t only originate in academic departments.

It is written to show how workers, in their full diversity, have taken collective action to shape Australian history time and again.

This book is an attempt to communicate the meaning and emotional resonances of unionism.

It is not a catalogue of strikes and industrial disputes, a listing of registered Awards, and nor is it a political polemic.

There are many moments of worker struggle that cannot be captured in its pages—moments that had a transformative effect on the lives of their participants, and that reshaped the history of this country.

Hopefully No Power Greater inspires more readers to consult the extensive literature on such moments that already exists – as mentioned, it is an entry point, not a final word.

To capture and explain the human experiences of unionism, the book follows the life stories and biographies of individual unionists from all levels of the movement.

The stories told are not always the expected ones.

They have been chosen due to their representative character, because of the importance of specific actions and moments of struggle to the broader development of unionism along the two arguments I previously outlined, and based on the availability of historical materials.

This is an approach that offers benefits in capturing the lived reality of unionism, and demonstrating how the movement’s humanising mission has endured across time, even while its meaning has been significantly adapted and altered by successive generations of unionists.

But the focus on individuals also has its dangers, especially in the study of a movement of millions that has defined itself by its collective principles.

The case studies chosen to propel the narrative in this book are not intended for individual valorisation, nor to accredit these select few with the accomplishments of the broader movement.

Rather, they aim to personalise and humanise the movement and to demonstrate a fundamental truth: that the emotional community of unionism is composed of individuals who have joined together to attain something they never could alone.

Rather than try to quickly capture the better part of two centuries’ worth of worker struggle in the twenty odd minutes I have left, I want to dwell on two representative examples of the dynamics I explore in the book.

The first may be familiar to this audience.

In April 1856 James Galloway, a leading Melbourne-based Stonemason Society during its campaign for the 8-hour day penned an angry letter to the Age newspaper.

His letter was in response to public statements by the prominent architect John George Knight, critical of the 8-hour day campaign.

Knight argued a reduction in work hours would increase the labour cost for construction projects, threatening the Victorian colony’s economy.

This was the result of an intractable law, Knight explained, as in his words: the ‘value of labor, like merchandise, depends on the supply and demand.’

He believed the Stonemason’s campaign distorted the normal functioning of this principle.

Galloway refuted this, arguing that Knight did not understand what motivated the Stonemasons in their campaign.

They did not want their value, like merchandise, to be determined by the whims of the labour market—by the inhuman forces of ‘supply and demand.’

The Stonemasons, largely British born, had migrated to Australia to escape the class-based privations of the Old World, not to replicate them. ‘

We have come’, Galloway insisted, ‘16,000 miles to better our condition, and not to act the mere part of machinery.’

I was really struck by that quote when I was researching this book.

‘Not to act the mere part of machinery.’

Reading through union sources in this era, I found that similar sentiments were expressed across the burgeoning movement time and time again.

Across industries and across the colonies, unionists would frequently invoke the idea that they were not being treated as human beings; but as machines, or beasts of burden, or slaves.

Union organisation to attain basic rights was conceived as a primary means to resist this dehumanisation, and to assert the fundamental humanity of the working person.

It is important to understand the context to this humanising claim.

This was a time of imperial expansion and largely unrestrained industrial capitalism, in which the modern understanding of human rights (including economic rights) did not exist.

Large numbers of labourers across the British Empire were treated as little more than commodities, and forms of unfree labour were rife.

While slavery was formally abolished in the British Empire in the 1830s, in practice it continued in many colonial contexts, including on the continent of Australia.

Australia also had the experience of unfree labour through Convictism.

Both industrial capitalism and the British Empire depended upon this commodification and unfree labour.

But it also required large workforces of ‘free labour’—working people who defined their status against the utter dehumanisation of slavery or convictism, who subsisted by selling their ability to work on the labour market.

In theory, they had the freedom to use the labour market as individuals to negotiate with employers on equal terms to get the best price for their labour power.

Workers frequently found that they were free to sell their ability to work on the labour market, but that market itself seldom worked to their advantage.

The inequality of the labour market stripped workers of their humanity. It reduced them, as Galloway lamented, to the status of little more than mere machinery.

This was a process of commodification: one in which human beings, working people, had their social worth and quality of life determined by the vicissitudes of the market. Subject to the inequity and dehumanisation of the unrestrained labour market, individual workers lacked bargaining power over wages and conditions.

The value of their toil was determined by the principles of supply and demand.

The first unions were an embodiment of the reality that the most effective means for the sellers of labour to elevate their conditions on this market was as a collective.

If they bound together, they could demand and negotiate a better deal than they would get if they acted alone.

As James Galloway warned a meeting of bricklayers during the eight-hour day campaign, ‘it was necessary that all should go together, because individually they would fail.’.

The union movement’s humanising claim was formed in this context, which allows us to understand the Stonemason’s struggle in a different way than we tend to have previously.

Galloway became a leading figure among the Stonemasons of Melbourne, alongside another recently arrived migrant, James Stephens – who is better remembered.

Together, they were pivotal in the refoundation of the Stonemasons’ Society in Melbourne.

The society’s core demand was the reduction of the working day to just eight hours.

It was typical at this time for stonemasons to toil for ten hours a day, six days a week (though they often only worked for eight hours on Saturday).

It is believed that Stonemasons on two worksites in Sydney in 1855 had the first success in winning a reduction in work hours in Australia. The problem was that these victories were limited to just those two sites.

A later eight-hour victory in Sydney was premised on a reduction in pay.

This helped inspire Galloway and Stephens and their fellow Stonemasons in Melbourne.

Melbourne Stonemasons met together early in 1856 and considered simply announcing a date upon which the eight-hour day would be standard across the industry.

It was decided to meet with employers to seek an agreement.

This meeting took place as a public meeting at the Queen’s Theatre at the end of March at which famously the workers and the majority of employers agreed to the eight-hour day.

The Stonemasons were joined by other workers in the industry, such as the bricklayers, carpenters, joiners, and plasterers.

At the meeting, Stephens, moved a motion warning that if ‘any employers should prove obstinate at the time appointed, they, the operatives could know how to act. They would only have to strike work’.

This declaration was met with a hearty ‘Hear, hear’ from the crowd.

It was decided that the new ‘system’ of work would begin from 21 April, to provide employers with time to adjust.

And so the eight-hour day was agreed by the majority of the industry with an alacrity underpinned motivated by a not particularly veiled threat of consequences—industrial action—if the stonemasons’ demand was not met.

But not all employers agreed.

There were two hold -outs who refused to allow a reduction in working hours if pay was not also reduced. One of these employers was William Cornish, who had been contracted to construct the Victorian parliament building on Spring Street.

The Stonemasons knew that these hold outs would continually threaten the new standard.

And would mean that some Stonemasons would miss out.

As Galloway explained in the Argus newspaper, ‘we considered that we were not justified in accepting the boon from our employers unless it could be universal in its operation, so that all contractors may have a fair chance.’.

On the 21st of April the stonemasons determined to take action to ensure that the eight-hour day was successfully introduced on those worksites where employers had agreed, and to put pressure on Cornish and the other employer to concede.

Stonemasons who were building the Quadrangle at the University of Melbourne, led by James Stephens, gathered together and marched into the city.

The procession ended up at the parliament house, where the workers there declared they would strike until the demand for an eight-hour day was met.

Ultimately, the issue was settled when the colonial government, which had contracted Cornish to complete the building, changed the terms of its contract to cover the costs associated with the switch to the eight-hour day.

This was a significant victory. While workers elsewhere had attained the eight-hour day, this is likely the first time that it had been won, through collective action, as the general standard across an entire industry without a reduction in pay

This victory also had a deeper resonance—one that reverberated across generations to come. The stonemasons were claiming their right to a life outside of work.

While proud of their profession and their social contribution, they argued that their lives should not be confined to this role alone. Framed in the language of civic contribution within the colonial state-building project, this was a reclamation of their humanity: an argument for the right to be regarded as more than mere machinery.

It was a formative episode in the establishment of the emotional community of unionism:, as a fundamental humanising claim was pursued, and won, through collective struggle.

It bound the stonemasons together as not just fellow professionals (potentially competing for jobs), but as a fraternity of unionists, acting together for their common betterment.

In August of 1883, Ellen Cresswell was testifying to the Royal Commission on “Employés in Shops”.

It was, in effect, a major investigation into the conditions that prevailed across Victoria’s factory system.

Cresswell was a Tailoress, employed at Beath, Schiess, and Co., which owned several factories, the most notable on Flinders Lane.

Cresswell spoke of the conditions that prevailed across the industry.

She spoke of long hours of toil, of employers seeking to hold down rates of pay, and appalling conditions.

She spoke of the common practice of outwork – the sending of work outside of factories for women workers to complete in the home. Because these women weren’t directly employed, they were frequently subject to hyper-exploitation.

Using the labour of Outworkers, Cresswell explained, was a common tactic by employers to hold down rates of pay. Tailoresses were not paid an hourly wage, they were paid piece rates – per item completed.

But Cresswell’s was not just a tale of woe.

The Commissioners were particularly interested in Beath, Schiess, and Co because it was at that company in December of 1882 that the unthinkable had happened.

The company had told its female workforce that it was cutting rates by 10% - this was on top of an earlier 10% cut just weeks before.

In this era, women were expected to be docile and compliant; to conform to gendered stereotypes of passivity.

The world of work was very much considered a male realm.

Among the colonial population, while male work was lauded as socially vital, women’s labour was often seen as a mere interregnum between childhood and childbirth, or perhaps an understandable but unfortunate response to the straitened circumstances of widowhood.

These attitudes fed restrictive employment practices that limited the work opportunities available for women, which then reinforced their subjugation within the household, as it largely rendered them dependent on a male breadwinner.

But the Tailoresses of Beath, Schiess, and Co defied these expectations.

Up until the 1870s, unions had predominantly been the preserve of white and male workers with socially recognised skills and expertise that were often in a short supply.

But as machines and new techniques of production changed working lives, a new swathe of workers considered ‘unskilled’, including women workers, also organised collectively, and sought to assert their own industrial power.

These workers brought substantial change to the emotional community of unionism and expanded the bounds of its humanising mission.

The strike of the Tailoresses shone a spotlight on the corrosive effects of supply and demand across the industry.

Beath., Schiess and Co. complained that competition among manufacturers had led to downward pressure on the payment of rates, and indicated they were willing to pay more, but only if all other companies did the same.

To achieve this end, Beath., Schiess and Co. encouraged Ttailoresses to form a new union to attain uniform standards.

The company did not anticipate the enthusiasm with which their workforce tooak up this proposition.

Early in the dispute, the company decided to retract the cut in rates, but was shocked when the Tailoresses responded that they were not content to return to the former status quo, they were now insisting on even higher pay than they had received before.

On 16 December 1882, a Saturday, 400–—500between four and five hundred women from across different factories in the trade assembled in a mass meeting to discuss their struggle and the actions required to press their claims.

It was at this convocation that Ellen Cresswell moved the motion:

‘That this meeting of tailoresses form themselves into a union for their mutual protection and improvement’.

The striking tailoresses were adept in communicating their message, and were able to gain a considerable amount of public sympathy.

The Trades Hall Council (THC) called on all unions to support ‘our sisters in labor’ and their struggle ‘to obtain a reasonable remuneration for their labor’.

Male-dominated unions donated at least £2,000 to sustain the strike, though some male unionists remained hostile to the very notion of women in the workforce.

On 21 December 1882, Beath, Schiess, and Co. agreed to the union’s demands, but with a condition: the union had to win the agreement from other employers in the industry to pay the same rates.

A mass public meeting took place at the Melbourne Town Hall to discuss the dispute in February 1883.

At this meeting, women workers at thirteen other factories determined to take strike action to force their employers to agree to union rates.

The strike expanded across the industry, and by the end of February 1883 a new log of conditions had been agreed between the Tailoresses and the newly formed Clothing Manufacturers’ Association, representing employers.

Continued intransigence from some firms required further negotiation, and a final agreement was reached in May 1883.

This was a success for the union, but it was not the end of the story. Individual manufacturers sought to get around the newly agreed conditions by increasing the amount of outwork they sent out of their factories to be completed in the home, work mediated by subcontractors.

Women workers had won a substantial wage concession through their own mobilisation, and this enhanced public sympathy for the strikers, and awareness of their industrial plight.

But crucially, these women workers had not just been docile victims, but had, through their own action, secured redress, challenging entrenched gendered stereotypes.

They had formed a new union, and were integrated into the broader representative structures of the movement (though this was limited by male unionists who continued to dominate).

They had extended the bounds of unionism’s emotional community by demanding their own place within it.

The Tailoresses’ action had also prompted the expansion of the Royal Commission into a broader investigation of work practices in factories across Victoria.

At the Royal Commission, Cresswell was asked if she believed there was a case to be made to create a “court of conciliation” to help avoid such disputes and enforce agreements.

Cresswell agreed, stating that employers took advantage of their workers – “I consider we are nothing better than white slaves with our employers.”

Such a Court was not created in Victoria, though the Tailoresses were able to win adherence to their log for the rest of the decade – until Victoria was drawn into the calamity of the international economic depression.

The early emotional community of unionism was constituted on the basis of exclusion as well as inclusion.

The Australian union movement was formed from within a colonial population during the British Empire’s invasion and colonisation of the Australian continent. The first unionists were skilled, white, male workers.

They created organisations to advance their claims on greater economic justice and recognition of their humanity within the imperial context. Their ideas reflected this reality.

Their humanising mission was proscribed by the racist and gendered attitudes of their time, which limited its scope and application.

In the decades that followed, the bounds of unionism did expand to the ‘unskilled’ and to women workers, but the racial boundaries were strictly policed.

Unions did not generate the racist ideologies of the British Empire, but they did reflect and perpetuate them in their own ranks, reflected in Ellen Cresswell’s fear of being rendered as a ‘white’ slave.

The story of the union movement’s emotional community is also the history of how those excluded workers came together, organised, and acted to challenge these exclusions, both in the union movement and in broader Australian society.

It is the story of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Nations workers , women workers, migrant/culturally and linguistically diverse workers, and workers from other vulnerable communities who, through their own activity, transformed the attitudes, practices, and beliefs of unionism. Their story expands our understanding of unionism and worker action.

The agency and activism of these communities is an integral part of the story of unionism and worker action in Australia. It is a history of struggle that deserves to be told.

As an historian, my first responsibility is to understand.

To try and understand the contextual factors that have shaped the movement.

To understand how unionists made sense of the world they lived in.

The ideas and attitudes they replicated.

The ones that they rejected.

And how workers in their unions sought to remake their world.

What motivated workers to create their own organisations.

To sustain them, and pass them on, from generation to generation to come.

That is not just a story of institutions, or of laws, or of tribunal decisions.

It is a story of human beings.

As grand, complex, paradoxical, and inspiring as human beings tend to be.

That full complexity is not captured in this book.

How could it be?

Unionism is a movement of millions.

No one book could ever capture unionism’s extraordinary history.

My hope with this book is that it will be an entry point for those who are wanting to learn about unionism and its relevance.

That it will communicate something about the human experience of unionism.

That it will humanise the collective.

And that it will demonstrate that in our own era of disempowerment, and the global economic elite finding new ways to dehumanise us and set us apart from each other, that the union movement remains not just relevant, but absolutely vital.

For all of us who want to assert our fundamental humanity against those forces that would strip it away, there is no power greater.