This week I was invited to deliver a talk as part of the “Understanding Victoria” historical series at Government House based on material from my new history of the union movement, No Power Greater, which is being released Wednesday May 14.

Booktopia are offering a special pre-order discount at this link.

For the series, I spoke to the following question:

How did Victorian workers assert their fundamental humanity and reframe understandings of industrial and economic rights in the late 19th century?

In August of 1883, Ellen Cresswell was testifying to the Royal Commission on “Employés in Shops”.

It was, in effect, a major investigation into the conditions that prevailed across Victoria’s factory system.

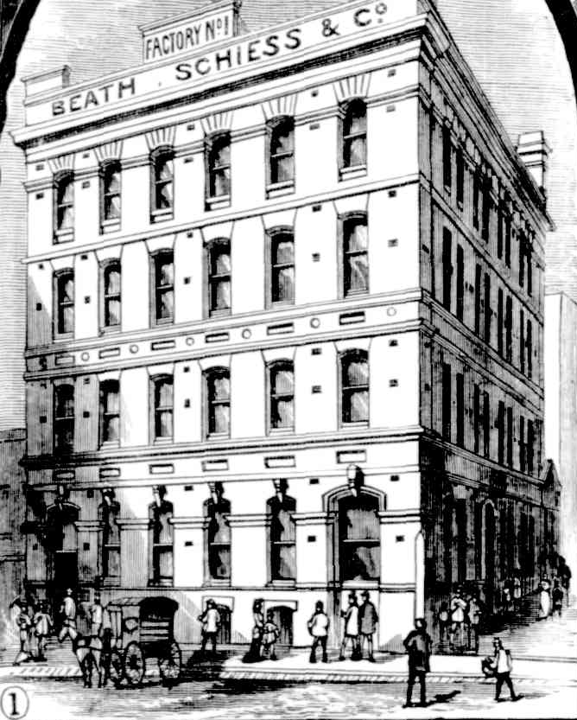

Cresswell was a Tailoress, employed at Beath, Schiess, and Co., which owned several factories, the most notable on Flinders Lane.

Cresswell spoke about the conditions that prevailed across the industry.

She spoke of long hours of toil, of employers seeking to hold down rates of pay, and appalling conditions.

She spoke of the common practice of outwork – the sending of work outside of factories for women workers to complete in the home. Because these women weren’t directly employed, they were frequently subject to hyper-exploitation.

Using the labour of outworkers, Cresswell explained, was a common tactic by employers to hold down rates of pay. Tailoresses were not paid an hourly wage, they were paid piece rates – per item completed.

But Cresswell’s was not just a tale of woe.

The Commissioners were particularly interested in Beath, Schiess, and Co because it was at that company in December of 1882 that the unthinkable had happened.

The company had told its female workforce that it was cutting rates by 10% - this was on top of an earlier 10% cut just weeks before.

In this era, women were expected to be docile and compliant; to conform to gendered stereotypes of passivity.

The world of work was very much considered a male realm.

The social expectations that colonial women would predominantly act as wives and mothers facilitated their hyper-exploitation, and undermined their industrial power.

But the Tailoresses of Beath, Schiess, and Co defied these expectations.

At the end of December 1882, a mass meeting of Tailoresses took place at Trades Hall.

Ellen Cresswell moved a motion at that mass meeting: “That this meeting of tailoresses form themselves into a union for their mutual protection and improvement.”

This was the creation of the Victorian Tailoresses Union – widely believed to be the first union of women in Australia.

Early in 1883, the strike spread well beyond Beath, Schiess, and Co – and involved Tailoresses from across Melbourne’s workplaces.

Eventually, a “log” of claims was agreed to between the union and a newly formed employers organisation in the trade.

This was a striking victory – but a fragile one.

Almost immediately some employers tried to undermine the log of claims, and the Tailoresses had to fight to force them to adhere to it.

At the Royal Commission, Cresswell was asked if she believed there was a case to be made to create a “court of conciliation” to help avoid such disputes and enforce agreements.

Cresswell agreed, stating that employers took advantage of their workers – “I consider we are nothing better than white slaves with our employers.”

Such a Court was not created in Victoria, though the Tailoresses were able to win adherence to their log for the rest of the decade – until Victoria was drawn into the calamity of the international economic depression.

In the 19th century, unions were formed with a humanising mission.

The earliest unions were industrial organisations formed by skilled, white, male workers, who sought to assert their fundamental humanity against the dehumanisation and the commodification of the untrammelled labour market.

It is important to remember this was an era without substantial social protections and with little to no industrial regulation.

The primary mechanism for workers to win rights that asserted their fundamental humanity was collective industrial action.

These workers complained of being treated as machines, or beasts of burden, or slaves.

In 1856, Stonemasons in Melbourne campaigned for the eight-hour day. In effect, the right to a life outside of work.

James Galloway, a stonemason leader, explained: ‘We have come 16,000 miles to better our condition, and not to act the mere part of machinery.’

In union campaigns, union forums, and the burgeoning union literary scene, such claims were repeated.

Labour was asserting a fundamental humanity against an industrial system that denied it, by valuing workers not as human beings, but as factors of production.

It is important to note that this was, in its time, a radical departure from the established industrial and economic orthodoxy: that wages and conditions of work should be determined by ‘supply and demand’ on the labour market alone.

It was also, as Marilyn has mentioned, in direct opposition to the widespread hyper-exploitation of unfree labour – a common practice in the British Empire as well as elsewhere across the globe.

This includes on the continent of Australia.

These early unions had a humanising mission – but an attenuated one, limited by the racial and gendered exclusions of the time.

Take for instance Cresswell bemoaning being treated as a ‘white slave’.

It is important to note that excluded workers undertook their own organising and collective action.

Sometimes, as with the tailoresses, they had some successes in breaking down these exclusions (at least to a certain extent) and claiming a place within the broader union community.

The union movement’s drive to assert the fundamental humanity of the working person was not limited to the industrial realm of collective bargaining and relations between employers and their employees.

One of the great turning points in Victoria’s history was the economic depression of the 1890s, and the series of bitter industrial defeats experienced by unions and the workers’ movement.

This underpinned the social reform of this era as new state-based mechanisms were devised to address the social harm caused by the market’s collapse.

Unions increasingly sought new legislative and social protections to substitute for sapped industrial strength – and to achieve the movement’s fundamental humanising claims.

In my new book, No Power Greater – I tell the story of Billy Trenwith, secretary of the Bootmakers union.

In that union’s 1884 struggle against outwork, Trenwith had argued: the ‘employers of labour cared no more for those who were working for them (nor indeed so much) than they did for their machines.’

In 1889 Trenwith was elected to the Legislative Assembly. He campaigned as a staunch liberal rather than a labour radical.

This was a time before a clearly defined and independent Labor Party in the colony, and unions had a strong historic connection with the forces of liberalism.

But within this broad alignment, labour retained its own aims – based upon its historic humanising mission.

And this included influencing the broader progressive liberal reform project in a manner that aligned with this mission.

In 1895, the liberal Chief Secretary Alexander Peacock responded to the continuing controversy over conditions in factories with a proposed amendment to the Factories Act.

This was intended to protect those deemed most vulnerable: white women and juveniles.

It went alongside punitive and racist amendments aimed at restricting Chinese labour.

Peacock’s proposal was to create wages boards in certain industries to set base wages for the vulnerable.

The month before Peacock’s amendment was tabled in the Victorian Parliament, the Melbourne Trades Hall Council had resolved that its position was that ‘the Minimum wage principle be extended to males as well as females’.

In other words, to generalise the minimum wage to all workers – not just those deemed the most vulnerable.

This would bolster the position of white men as wage earners, who had lost industrial power as a result of the depression.

This was then pushed by Trenwith and other union-backed MPs in parliament.

Peacock rejected this, stating his intention was only to protect ‘the weaker sections of the community’.

Trenwith rose to speak in response, stating: ‘That reason applied to all descriptions of labour.’

Trenwith made the point that amid the depression, organised workers could only protect their position through deeply damaging industrial disputes – and often could not even do that.

Social protections, hence, should be extended to all workers.

The new boards would operate in each named industry as ‘a perpetual board of arbitration’, fulfilling a principle that was not just ‘economically sound’ but ‘humane.’

This was opposed by Peacock and some of his supporters who still held to the general idea that industrial relations should remain free from government interference wherever possible – only the most vulnerable should be protected.

It was also opposed by conservatives who were hostile towards intervention into the labour market by the state.

The Member for Hawthorn, Robert Murray-Smith, a proponent of laissez-faire economics, rose to argue that government intervention would ‘destroy the clothing trade altogether, so that the employés, instead of getting small wages, would not get any wages at all.’

To which Trenwith immediately interjected, ‘Will people go without clothes?’

The union-backed amendment passed, and wage boards in four industries were generalised to cover all workers within them.

This, as Marilyn has pointed out, created the world’s first compulsory legal minimum wage. This minimum ‘reinforced the equality of citizenship’ that was at the centre of this progressive liberal worldview.

But it also reflected a fundamental and long-term humanising mission being pursued by unions against the dehumanisation and commodification of the unrestricted labour market.

The wage boards began operating in four industries the following year.

It is worth noting that one legislator in this debate who ended up supporting the union proposal had long been a progressive liberal opponent of government intervention into industrial affairs.

His mind had changed through witnessing the devastation of the depression, and through this debate.

His name was Henry Bournes Higgins and just over a decade later his Harvester decision would bring the philosophy underpinning the creation of the first minimum wage into the national system of wage fixation.

Among the factors that led to these historic developments was the active intervention of working people as they sought to assert their humanity against the dehumanisation of the untrammelled labour market, and to create the industrial and social mechanisms to protect it.

The Melbourne launch for No Power Greater will be held on Thursday 29 May, 6.30pm at Trades Hall, Carlton. It would be fantastic if you could join us!

You can RSVP to the event at this link.