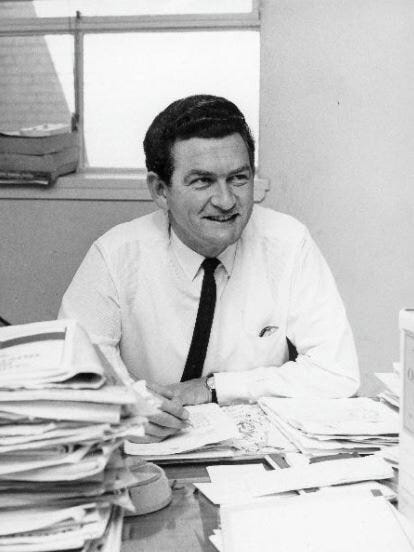

Bob Hawke was one of the most interesting and influential thinkers on Australian industrial relations. As a scholar, as ACTU Advocate, as ACTU President, and finally as PM, his career was bound to the system of arbitration – first as a critic, then as a key practitioner, and finally, as the augur of its transformation.

Ever since I first read Blanch D’Alpuget’s criminally underrated first biography of Hawke, detailing his career at the ACTU, I have been fascinated by Hawke’s industrial career and how it shaped his prime ministership.

I get to tell really fascinating parts of this story in my upcoming book on Australian union history, No Power Greater: A History of Union Action in Australia (released this May, available for pre-order now).

But, as is always the way, there was so much fascinating research I had to leave out of the final version of the book, because apparently books are less popular when they are 2,000 pages long.

Rather than let it go to waste, I wanted to put some of it together in this short series on Hawke’s career in the IR system, from scholar to prime minister.

This is not a biographical work, and will be limited in scope to this one thread of his life – but I hope will provide insight into Hawke’s career, but more broadly, the functioning of Australia’s unique industrial relations system in his time.

There was a great deal of suspicion about Bob when he joined the ACTU as its Advocate and Researcher in 1958.

The ACTU at that time largely represented Australia’s blue-collar unions (separate peak bodies existed for white-collar professional and government employees). Hawke was not just an academic, he was a former Rhodes Scholar. He was derided in some sections of the movement as an ‘egghead.’

Even ACTU Secretary Harold Souter believed he would last only a couple of years before he was replaced with ‘someone else from the universities.’

Against expectations, it was the beginning of a 22-year long career at the ACTU – a career that launched Hawke to the Prime Ministership.

How did Hawke navigate this unusual pathway to the ACTU?

Hawke was born at the end of 1929, just as Australia was snared in the international cataclysm of the Great Depression. Aged 10, Hawke’s family moved from South Australia to Perth. Hawke later gained a degree in Arts and Law from the University of Western Australia in 1953.

1953 turned out to be a defining year for Hawke.

His uncle, Bert Hawke, was elected as WA’s Labor Premier. Bob would later refer to his desire to replicate this family success on the national stage.

Bob was also selected as a Rhodes Scholar, departing for Oxford that year.

Atypically for that institution, he determined to complete his thesis on the Australian arbitration system and its basic wage (more on this below).

1953 was also the year that the Arbitration Court handed down a decision that so enraged Hawke, it would become his life mission to rip it to shreds.

He later recounted, ‘I steeped myself in that decision as I had no other and determined to destroy it.’

What was it that infuriated Hawke so much?

In the 1953 decision, the conservative Chief Justice of the Arbitration Court (the industrial tribunal) engineered a fundamental shift in how wages were determined for millions of Australians.

When I say Kelly was conservative, I mean it. He was close to Bob Santamaria, a leading figure among the movement of right-wing political Catholics who would precipitate the infamous Labor split and forge the DLP within a few years. Kelly ascribed to the bucolic nostalgia of the National Catholic Rural Movement, and advocated the virtues of a rural based peasant economy. No, seriously.

Among other sins, the 1953 decision abolished a long-standing practice of wages being automatically increased to alongside the rising cost of living.

This infuriated Bob, and his scholarship was directed towards undermining the credibility of this decision, and the assumptions that had informed it.

In 1956, the University of Western Australia’s Annual Law Review published an extensive article by Hawke titled “The Commonwealth Arbitration Court – Legal Tribunal or Economic Legislature?” in which he articulated the terms of his critique. You can read the full article here.

In the piece, Hawke provided an extensive historical account of the Arbitration Court, intended to pull apart the justifications and reasoning of the 1953 decision.

Before the 1890s in Australia, industrial relations was largely considered beyond the realm of government intervention.

Wage outcomes were the result of direct bargaining between unions and employers where unions were present, and the vicissitudes of the labour market where they were not.

The massive global economic depression of the 1890s spurred deep and bitter industrial conflicts in that decade.

Many in the labour movement looked for alternatives (political and legal) to compensate for eroded industrial strength.

At the same time liberal reformers dedicated to building a new nation abhorred industrial conflict, and sought to find a new mechanism to ameliorate class antagonism.

Hawke doesn’t say this in his account, but these liberal reformers and their industrial reforms were shaped by the exclusions of the time. Their reforms were intended to bolster the position of white male workers as citizens of a new nation built upon dispossession, racist exclusion, and gender inequality.

Liberal reformers advocated for a new industrial court/tribunal system that could intervene into the realm of industrial relations to ameliorate class division by ensuring just outcomes for industrial disputes (this was the theory, anyway).

After defeats in the disputes of the 1890s a growing number of unions came to support this idea, and it inspired the creation of a federal court of conciliation and arbitration (which I will just call the Arbitration Court).

This Court was always controversial. It was legislated for in 1904 after a fierce debate – though that probably undersells the controversy. As Hawke described:

‘Seventeen months and eight days elapsed before the Bill received royal assent and in that time it acquired an impressive list of casualties – one minister resigned, two governments fell, and in fact it was steered through Parliament under four different Prime Ministers.’

The court was initially designed with a limited jurisdiction, where industrial disputes took place ‘beyond the limits of any one State.’ But over time through practice and judicial interpretation, this ambit expanded massively.

The court would hold hearings on disputes where unions and employers would make their case before a Justice (later several Justices) who could then hand down a binding decision outlining wages and conditions – these were called awards. It could also approve voluntary agreements between unions and employers and give these agreements the same legal status as awards.

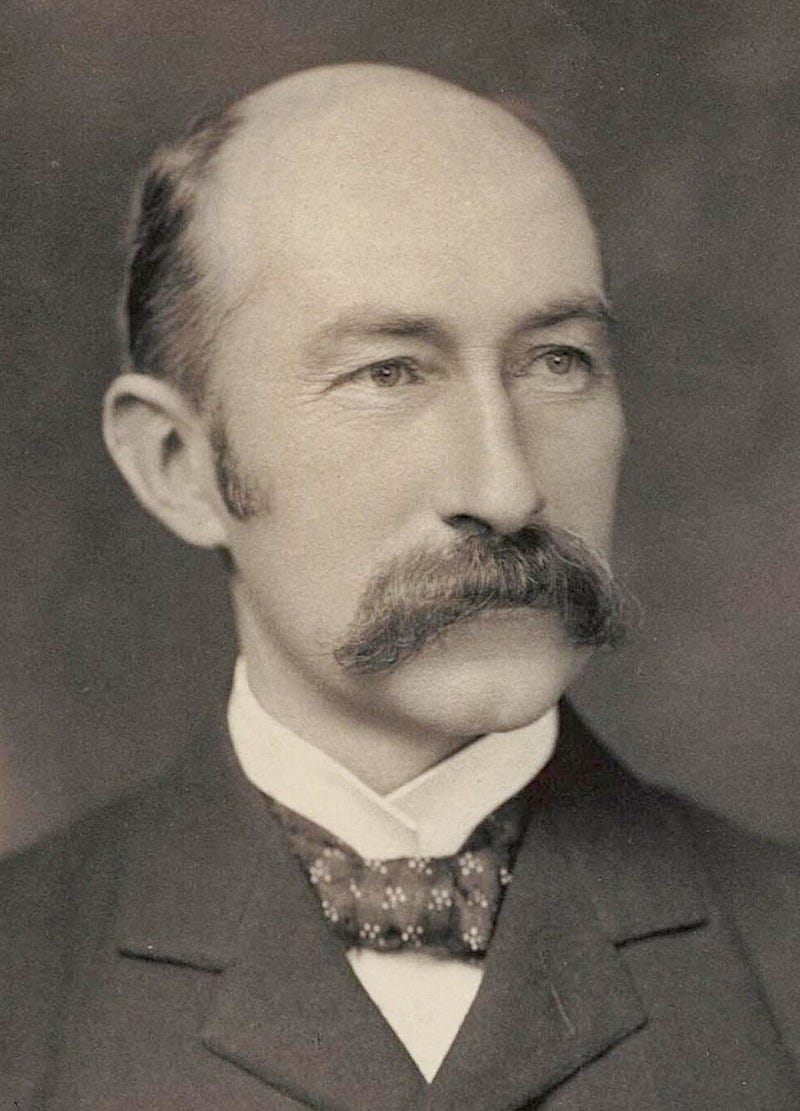

In 1907 the second President of the Court, Justice Henry Bournes Higgins, handed down a special ruling in a test case that proved to have defining consequences.

An employer applied under legislation at the time for exemption for an excise tax, which he could only receive if Higgins signed off that this employer paid a ‘fair and reasonable wage.’ The employer was Hugh McKay who owned the Sunshine Harvester company (which the Melbourne suburb of Sunshine is named after).

Higgins heard testimony from McKay and ruled that he did not pay a fair and reasonable wage – which would be an amount that would meet ‘the normal needs of the average employee regarded as a human being living in a civilised community’.

In other words, a fair and reasonable wage was one that a worker could actually afford to live on. This was a new principle that came to be known as the ‘social needs’ principle, and it informed a wage rate Higgins set in this case and others that followed that came to be known as the ‘basic wage.’

This was, in effect, the principle for a new minimum wage, and it was one that Higgins consistently applied in the years to come.

Higgins would later describe this ‘basic wage’ as ‘sacrosanct’, and beyond bargaining. It was a limited wage that reflected the basic needs of an ‘average employee,’ Higgins also set a second rate that was intended to remunerate for skill, known as the ‘margin’ rate. This rate, Higgin made clear, was very much up for bargaining.

This decision was also marked by the social exclusions mentioned above. When Higgins referred to a worker, he conceptualised a white man who acted as the breadwinner for ‘his’ family. In a subsequent decision, he set the basic wage for women at 54% of the male rate. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers were usually denied the basic wage due to racist exclusions in other legislation (though to be fair to Higgins, for all his faults, he did protest this inequality).

The Sunshine Harvester decision set the basis for a new minimum wage – but it was not a minimum wage as we know it today. It did not apply generally to all workers. Rather, it was a means through which Higgins determined how to set wages for the cases that came before his court. It would later be generalised more broadly (but we’ll get to that).

The importance of the Harvester decision was conceptual. Higgins hard argued that the ‘higgling of the market’ alone should not determine wages. The ‘social need’ of a worker also needed to the primary factor taken into account.

But this did not mean that Higgins had no other priorities. A secondary consideration was enunciated through Higgins’s cases: the ability for an industry to afford pay rises. In a later case, Higgins pointed out that it was necessary for wage rises to be affordable across an industry, which came to be known as ‘capacity to pay.’

Higgins made no allowances for individual employers within an industry who stated they could not pay this rate. His general view was, if your business model does not allow you to pay your workers the basic wage, you don’t have a very good business model.

In a later case, Higgins suggested that this question of affordability should apply only to the ‘margins’ payments for skill, not the basic wage.

While Higgins acceded to this concept of capacity to pay as influencing his decisions, Hawke argued that for Higgins this existed as a ‘passive criterion setting some upper limit which was not in question’ – while the determining factor in his decisions remained a wage that ensured a working man could live in a civilised community, with all the social rights and obligations that was deemed to entail.

In the 1920s, the jurisdiction of the court gradually expanded far beyond its original ambit. Unions would increasingly initiate disputes/claims in multiple states to be able to gain coverage by the federal court.

After much review of the basic wage level, the Chief Justice who succeeded Higgins instituted a system of automatic indexation increases – this meant that rather than relying on taking a case to the court for an increase premised on a dispute in each circumstance, unions that had its coverage would gain automatic wage increases across the economy.

For the next decade this was the general trend of the court as its powers and influence expanded in practice. Automatic indexation proved a boon to many workers. While both the ‘social need’ of the worker and the ‘capacity to pay’ informed judgements, the former tended to predominate.

This changed during the Great Depression.

In 1931, the Arbitration Court instituted a 10% reduction in the basic wage, a decision based on the parlous economic circumstances, and the erosion of the economy’s ‘capacity to pay’.

Through this decision, Hawke argued, the Court had exceeded its ambit and decided to ‘discharge the function of economic stabilizer in a situation of acute crisis.’ And it had done so through privileging the concept of the economies capacity to pay over the social need of the worker.

And so the balance between the two concepts – ‘social need’ and ‘capacity to pay’ – altered in this period, though the court continued to draw on both to inform its decisions. Until, that was, 1953.

For Kelly, the trenchant conservative, the emphasis should be on what business said it could pay. This fitted well with his weird desire to drive workers into the countryside to establish a new agrarian class of labourers. But not so well with, you know, the realities of Australian economic life, and the interests of millions of workers who depended on their wages to, you know, survive.

This is where Hawke’s severe criticism of the 1953 decision came from.

For Hawke, this decision ‘marked the final stages of the unmistakeable evolution of the Court into an institution affecting, fundamentally, the whole economic and social life of the nation’

Within this expanded ambit the Court had awarded itself, Hawke argued it was now also privileging the ‘capacity criterion as the positive determinant of the basic wage’, ignoring the social realities and needs of the worker.

While doing so, it had, the scholar continued, ‘been hampered by the lack of any ready-made index whereby the criterion can be easily translated into an appropriate wage rate.’

In other words, it did not have or rely on the type of modelling necessary to make such decisions, not did it have the economic expertise to interpret such modelling even if it did.

Hawke was outraged, and it was palpable in his writing. His scholarly work teeters on the edge of polemic.

His conviction in these points, his desire for justice, and his belief that the 1953 decision struck a blow at the very heart of this basic egalitarianism, brought Hawke to the ACTU. He did not want to be an observer, providing academic review. He wanted to be involved. He wanted to be a part of it. He wanted to make a difference.

Next time – we will look at how he did so as the ACTU Advocate.